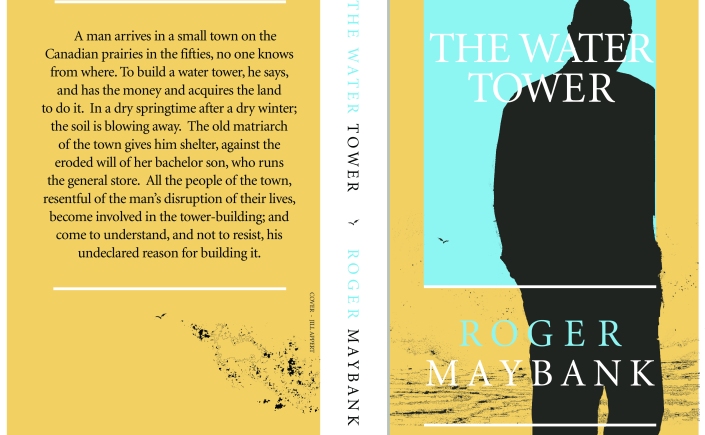

THE WATER TOWER

by Roger Maybank

CHAPTER ONE

Hilda pressed her forefinger against the ramp of thick frost at the bottom of the window until it was smooth and slippery from melting and her finger was cold, and watched the man climb down clumsily from the morning bus, holding his suitcase in his arms. He didn’t look very steady on his feet. He swayed a little as he waved to the bus, and coughed in the exhaust it swirled up around him. She ought to have some music on for him, she thought, in case he didn’t feel so very cheerful, arriving in a strange place when it was practically still dark. She felt the globe of coffee to make sure that it was nearly hot, and she put some nickels in the juke-box, thinking she would have to remind Harry again to buy some new records; but the man didn’t seem to notice that there even was a cafe. He was still standing where the bus had dropped him down, as if he couldn’t make out exactly where he was, turning his head first one way and then the other, looking at all the dead-looking buildings on the other side of the street. He had dropped one of his gloves on the ground and was rubbing his bare hand with the other, but not as if he knew what was wrong. He ought to come inside and keep warm until people were up. It would make a change from Mr. Wilkinson just sitting and smiling with never a word to say. It would keep her awake till Josey came.

Probably he was a salesman, though he didn’t somehow look like one, and he wanted to get the feel of the town before people started appearing. Or he could have relatives here, of course, though nobody had said they were expecting anybody. He seemed a big kind of man under his clothes, not so old either, but even when he turned her way she couldn’t see his face so well for his frozen breath drifting up in front of it. And he had a kind of limp, she could see that now that he started walking up and down a little;; like one of his legs wasn’t as long as the other. But she couldn’t make out which one it was, because he seemed at the same time to be stretching himself up like there was something over the buildings across the street that he was trying to see, but he wasn’t seeing it. He almost fell over his suitcase, and noticed his glove on the ground and picked it up, and started jumping up and down in one place, but turning round and round. When he was facing the cafe for the third time he saw her at last and stopped jumping and straightened his fur hat and grinned. She moved back from the window and put Mr. Fitts’ soup on the stove to heat. The man came into the cafe, pushing his suitcase through the door ahead of him and followed by the beginning of a cold wind that was rising.

“There isn’t any elevator here,” he said, still breathing hard from his jumping. He pulled off his fur hat and sat it on the counter and took off his heavy overcoat and unzipped his flight boots and sent them flopping across the floor. He was bald, but he was a strong-looking man all right, and the thin shirt he was wearing was wet with sweat.

“You’ll catch pneumonia,” she said. “You must wait until you stop sweating.”

“That’s a new coat,” he said. “And a new hat. And new boots. All good stuff. First sight’s important. Why isn’t there a elevator here?” He had a funny hoarse voice, but she didn’t mind that; it was his eyes being such a pale blue and not moving in his face that the sweat was trickling down. She put a cup of coffee in front of him.

“There is one,” she said. “Only it’s not a real elevator, it’s just a kind of warehouse.”

“I didn’t see it. I’m short, of course, but I can jump till I’m like six feet almost, so I should’ve seen it from where I was if it’s any size.”

“They say it’s not big,” she said. “Not big enough, they say. They still must load grain from trucks usually. Except this year it’s almost empty because the harvest was not so good last year, so there’s none couldn’t be shipped away. When it’s bumper, lots has to be kept there till spring.”

“Small, eh?” he said. “Not so big as the big building down the street? Taller, maybe. Taller? Just to get an idea.”

“That’s the hotel. That’s the biggest building in town, only it’s not used any more. The elevator’s not so big. You want to see it? You go out and turn right, and turn right at the first street you come to and you keep going. It’s by the edge of town. You know Mr. Wilkinson? He’s the agent. I think he’s not up yet, but he’ll be coming in for coffee soon enough. He always comes.” He was looking at her all the time, but his eyes were blinking more than they were.

“I guess I don’t want to see the elevator,” he said. He was swaying a little on the stool. “Maybe I will later. I’m not in any hurry, I guess, to see anything.” He pushed his half-full coffee cup away along the counter and pulled his fur hat towards him and laid his head on it and closed his eyes. “If it’s all right with you,” he murmured in a blurred voice, and then he was asleep. She stood where she was, watching him, until Mr. Fitts’ soup was hot enough to be cool enough for him to eat without too much complaining when she got it to him. Then she locked the cash register, just in case, and stopped the juke box playing, and put on her coat and carried the tray out into the cold windy street. Half an hour later, when she was making Josey’s breakfast, the man sat up and blinked at her.

“I just conk out sometimes,” he said, rubbing his big hands all over his face. “Where am I going to stay, d’you think?” He watched her fill up his cup with coffee.

“Is it for long? There isn’t a hotel since the big one closed. People don’t usually have a reason to stop here.”

“I guess there’re plenty of free rooms. It’s for a good while. Maybe I’ll just wander around and get the feel of the place.” He pushed his feet into his flight boots, leaving them to flap unzipped, and struggled into his coat.

“There’s not much for seeing,” she said, while he drank his coffee down. “It’s a small place. Mrs. Ledbetter maybe has a room.” He was already red in the face and beginning to sweat from the clothes. He opened the door and Josey ducked in past him.

“I’ll just take a look round,” the man said. “I’ll leave my bag here, eh?” He laid his hat carefully on top of the bag and went out, with Josey watching him and frowning.

“He’s going to be staying a while,” she said.

“He can’t walk straight,” he said. He sat on the stool where the man had been sitting, and then shifted to the one beside it and looked back at it suspiciously, it must be still warm from the man. “What’s he want here?”

“I don’t know,” she said.

*

Waking as usual just in time to silence her alarm clock before it rang, Amanda Purl listened for the music which she thought she had heard while asleep, but no trace of it remained. She lay on her back, unmoving, and listened to the boards creaking throughout the house and the faint wailing from one of the livingroom windows, and waited for the sleep in her head to settle out. She had no right to blame her aunt, she thought, she ought not to allow herself: if she had left the radio on it would still be on. The music must have come from somewhere else. From within herself, most probably, since the sense of it had been so keen.

The early sun glowed through her lowered blind, as warm as the air in her room was cold. A slender beam reached all the way in, to her very bed, lighting a patch of the maroon counterpane like a jewel, so that she couldn’t refrain from touching it with her fingertips though she knew she oughtn’t to delay. There would be other mornings now that the winter was dying; it would always be light when she woke, she needn’t be loth now to remove her hand from the clear warmth of the sun.

She heard her aunt’s muffled snoring, which gave her strength; she was younger and stronger than that. She inhaled the cold fresh air as deeply and slowly as she could, tensed her body from head to toe when her lungs were full, relaxed and exhaled as gradually as she could. Ten times, feeling the better for it as usual. Then she folded the bedclothes back from her throat, sat up, folded them down to her knees and slipped her feet over the side of the bed into her waiting fleece slippers.

She shivered, and realized that she had just been gazing at the glowing yellow of the blind, watching it ripple faintly as eddies of air filtered through the three holes in the storm window from the rising wind outside, thinking what a beautiful colour it was; which it was, of course, there was no denying it, but it was hardly the moment for looking. There were others to think of and, besides, she might easily give herself a chill.

She lifted her bathrobe off the brass knob at the foot of her bed and wrapped it round herself, and listened for a moment to the loud rattling of the back storm door. Not that there was any point now in reminding Frank of the times he had promised to put it right. It would soon be coming down to let the warm air in, and she might even find that she missed the noise after a winter of hearing it whenever there was a wind. She raised the blind and lowered the window and blinked into the rising sun, beyond the road and the flat fields and the frozen ditch of a river. The wind was certainly rising, which was a good thing; it would bring in the spring the sooner, and there would be a month or two at least when it would be neither too cold nor too hot, when she would be able to dig her garden and tend it and hope for the best, even for the rose tree which she should never have planted, as she knew as well as anyone. Yet if it died she would plant another, though they thought her foolish, because with care it might be kept alive.

She thought that she was beginning to feel dull, which would help nobody. Her aunt was still snoring, as if nothing could wake her except the wind crushing the thin walls of the house and blowing them away. She walked to the bathroom and pumped the cold March water into the basin and plunged in her hands and soaped and splashed her face and dried herself vigorously until her flesh tingled. When she felt as clean as the wind outside, she settled herself on the stool by the window and began to brush her hair.

The garden didn’t look like much now, she thought, but it was better than it looked, all the same. It wasn’t merely a patch of prairie with a fence around it. It would show itself when the snow on it now melted into the ground. The sunflowers particularly were always very handsome in their central circle, taller than she was by a good deal, almost as tall as small trees.

There was that sound again. She stopped brushing her hair. It was music, certainly, and it seemed to be the same music she had heard on waking. At least it felt the same, though with the wind whining at the window and the whole house creaking, she couldn’t make out the tune. She couldn’t see anyone either, nothing but the open ground between her house and the beginning of the town proper, and the buildings there, with their long black shadows on the snow and the smoke blowing out of their chimneys. Nobody was out yet; nobody except Mr. Jessop ever was at this time of year, and if he could make music he had certainly never shown it. She stroked her brush through her hair slowly and tried to make out where the tune, such as it was, was coming from. It was unsettling, and she thought it would be better these days if she were not unsettled. She laid down her brush and waited until the electricity stopped peppering through her hair, and then braided it and wound it up against the back of her head. Before her aunt had grown old, she had had thick hair too. And a figure, come to that.

The music had stopped. There was only the wind, the winter wind she liked, however cold it blew. Any wind for that matter; even a hot one full of dust was better than none at all. But the end of winter was always an uncertain time; she would do well to keep a close watch on herself, and not let her aunt see that her time had come at last.

She dressed herself in her bedroom, and cleared her aunt’s dirty late-supper dishes off the table in the kitchen, and sat down to correct the week’s spelling test and wait for the water to boil, while the sun streamed in.

*

Hiram Jessop arrived back at his drug store well after eight o’clock, his fingertips still numb from the frozen earth. He ought to have gone right into the cafe, he thought, or gone right past it. It was half-way measures ruined a man. He pushed open his front door with his foot and made his way across the small dim room to the counter. Hilda had looked surprised, seeing him standing in the doorway, as if she saw a connection already. Because she saw him taking an interest, as like as not, when she didn’t see that he had any reason, since it wasn’t his day for checking the accounts. It was habits that caused the trouble, you had to be on guard against them, they showed people what you were. But as long as it was only Hilda who noticed, he was all right, she wouldn’t say. They claimed her father was the same silent kind. Mother the same, more like; Indian blood was as powerful as sap.

Ducking under the counter, he piled his lumps of earth in the crook of his left arm and fished out his key with his free hand. In the room behind, he stopped to inhale the smells of himself. They were quieting. He needed quieting. It was all happening too quickly, he thought, peering at the sun pouring in through the ragged hole in the drawn blind. He hadn’t had time to get ready. A lot of the snow would be carried off in vapours and too much of the rest run off into the river. No good for the plants, no good for anybody. If there wasn’t a good deal of rain in the spring they were all going to find themselves with a bucket they couldn’t fill. Better no bucket at all if you didn’t have any water. The bigger the empty bucket the worse off people thought they were. But it was too late by a long way to tell Maggie. She was probably laughing anyway, as usual, seeing him with troubles. Her troubles.

He had better carry the clods into the dark room, before any seeds they had dropped out on the floor, no good to anybody. It didn’t look as if there was much in them, not at first glance, but they came from a better place than most, and there was something everywhere. Though they grinned and made their little jokes, of course, seeing him out again for the first time in the year. He lifted his tumbled blankets back onto his bed with his boot, and glanced at Mr. Fitts’ empty bottle on his desk. He couldn’t make up any fresh mixture now. The old man would just have to hold it in by himself, or run. Teach him patience like the tortoise, and not to start complaining to Hilda every time his medicine was delayed. He would make it up when he was feeling more easy, when he knew better how things were going to go. Nobody could expect him to have a quiet mind after so many years of making ready, and now suddenly the time had come, and so far as he could see it was the wrong time. He raised the latch on the small door to his dark room, and stooped to go through, though he knew he didn’t need. Habits didn’t matter where nobody could see.

He breathed in the warm dampness, feeling for the box he wanted. They could talk all they liked about the strange man, and make up their stories. The more stories the better. Though they had only seen him from a distance so far, walking round; only Hilda and Josey had seen him close. They’d talk this way and that. He couldn’t have come here without a reason, could he, so they’d be talking about that. And waiting for Harry, to have a chance to ask him what he thought, so they could think themselves. He crumbled the earth, listening to the hard ice-crumbs hit against the wood of the box. Fresh and cold and black it was, earth like a virgin put in a grave, ready to rot and send up fumes of heat and swelling. So other things would grow. And then other things and then others. His hands felt cool and hot together, hot from the ice. People thought probably he did it in test-tubes, mixed a few dried seeds. But the smell spread all over, not now so much, but when it was hot. They mostly walked by on the other side of the street then, when the smell started leaking out through the walls. Bella more than the rest of them, he had seen her, she wouldn’t even come near the place now. Too strong for her. Scared of things she didn’t know. They all were, come to that. But they were going to have one soon, all the same. And they wouldn’t know even then how it could happen. If the old woman let it happen, that was; it all depended on her.

He felt for a flat where roots were growing, smelling rank. He rested a hand on each end of it and leaned over and breathed the smell in as deep as he could. He had to remember that he was secret, that nobody could see him, or nothing would work. He wasn’t even in the background, he wasn’t there. He would be like Harry if they knew what he was. And Maggie would laugh harder and call him a fool. He couldn’t be rid of her if he lost his head.

He was half-asleep from the rich smell of everything. He nearly lost track of himself, and seemed to be floating; but he heard the faint echo of somebody limping on the sidewalk planks outside, and he heard from a long way off the ringing of the bell on the counter in his shop. Then he started awake at the thumping of a heavy hand on the counter itself.

*

“He’s looking for a place to stay,” Willa Gleave said over the telephone. “That’s what he told Hilda. But he’s not making much of an effort, if you ask me. He’s walking round the town, all right, but he’s not asking anybody. I’d take him myself if it wasn’t for Ray. Every little bit helps, particularly with Alvin saying all the time he’s looking around for some other job, being bored, you know, the way he is. Not that I’ve any complaint against Ray, he’s very regular; but I suppose this man’d pay a bit more, being a stranger. He’d want to feel at home, I expect, and with a family round it’s more friendly, isn’t it? Lord knows, he must be feeling like a fish out of water the way everybody goes round peering at him. I don’t think he’s so very strange myself. Why shouldn’t he stop in town if he wants to? Of course it’s not as if Ray was a full brother, but still, family’s family. I expect he’ll find somewhere all right.”

*

Harry Otterdown placed his foot on the edge of his desk and tied his shoelace, thinking that it was lucky that his arms were as long as his legs. In proportion, that was, everything in proportion. And there seemed to be no opposition at the moment; his other leg supported his body placidly, the shoe was

neutral, didn’t seem to feel unpolished, the lace itself was friendly, and even his hands, though priding themselves a little on being the same capable hands, however long his arms, behaved like part of the whole. If anything, it was the arms themselves which were taking up a slight separate attitude, the result maybe of being commended for their length. Reactions were so swift and unsure; he never knew what anything would say to praise or blame, they all sported subtle smiles of misunderstanding. All praise to the mouth, for it could be kept closed, gating wayward thoughts, sending them back to be edited for sense and style. There was no use having power if it couldn’t be controlled. Hearing and smelling were almost as useless as feeling; seeing was like talking, it could be stopped. Thinking was worst of all.

He sat down at his desk and warned himself of the dangers of free thought. Since he was lucky enough to have free moments, they ought to be better spent. They ought to be used for sifting the wheat from the tares, for finding out who and what were on his side, and marking the rest for burning or betrayal when the time came. That was the passover principle, a sound one enough; but the question was not so much his enemies, since all could be that, all right, could be turned into that or, at worst, false friends, if he wanted to be left alone. The question was from the other side: was he himself the first-born in danger, or the first-born spared? Or only later born, only looking on? Not that it mattered at the moment, but it was right to be ready. Many a king had fallen on a clear night.

He riffled through the nearest papers on his friendly littered desk, thinking it early for philosophic reflections. Or late, since the usual time was in bed after fitful nights. The usual pastime for the mid-morning was quiet; and for that matter he was quiet. It was the others who were unquiet, stirring up eddies all round him with their watching of the stranger wherever he went. As if there were something suspicious in his spending the morning wandering round the town. Though Mr. Fairling sometimes did, and nobody complained. Jessop wandered from thaw to frost, and nobody cared. They were all very possessive, it seemed. It was their town; the stranger should make his intentions clear.

On the other hand, not to be harsh, seeing both sides of the question, seeing with their eyes, curious, suspicious, doubting: what was there to interest him, eh? Since he claimed to care only about elevators and found theirs too small. Couldn’t find it at all in fact, but jumping in the main street wasn’t the best way. If he didn’t like how the town was arranged, nobody was asking him to stay. He didn’t need to get off the bus, did he? He could have ridden through, without paying much more, to a town where he could see the elevator by jumping in the main street. He had a nerve finding fault with their town in the first minute he arrived, and it being practically pitch-dark at that.

To interpose a cooling counsel: wait-and-see. He would doubtless reveal his purpose in the fullness of time, when everyone could decide whether or not he cared. In the meanwhile, accept him as a diversion in the dead between-season.

Pleased with his moderation, he shifted his chair round so he could gaze from his official perch over his store below, where only Maida was, the only

citizen he had for now; though beyond the windows, in the bright main street, Mrs. MacNamara was passing, and Ray was crossing over to the cafe, where else? There was a wind out there, sweeping along, but here there was only the noise of the stove keeping him warm, and the soft sound of Maida filing her nails. He leaned forward to rest his chin on the wooden railing, and reached a mental hand into the air above her and the blouse counter she was leaning against, and laid a blessing on her and all her works. She was a quiet girl, no trouble at all. Frank knew how to raise children all right. It was a pity she wanted to marry and go to the city while Mavis was not yet full-breast grown and Maureen was only a gawky child-thief. Still, at Maureen’s age Maida had shied mechanically when a hand was raised near her.

“That’s seven times he’s been past so far,” she said, not looking up. “He’s been nearly everywhere in town, looked at everything.” She still had a general interest in the passing show, what more could a man want? She was pretty, and she liked listening more than talking. If she had a telephone on a party line, she wouldn’t ask to move for hours. An object lesson to them all.

He seemed to be taking a very moral tone this morning, with very little ground for doing so. When had his own behaviour been impeccable? Perhaps, after all, the stranger was having his effect: the whole town was under surveillance, Maida said, but he felt the gaze personally. The gaze of an assessor, which the man might well be, why not? Nobody so far had come up with a better suggestion. A travelling salesman they said who had never had to deal with them and their smart cases and evasive smiles. A land surveyor? The land was already surveyed. Surveyor for a road, then? Or for a bridge across the Rat, a simple spanning. Or both. The town might find itself on a cross-country highway. It might not be worthy. They had had to send out a man to discover. When he had finished with the site, he would work his way through the citizenry, querying, jotting notes, assessing each. That was it, he did well to prepare himself: he was under scrutiny as the town’s first citizen, its reeve and judge. The stranger had not come by accident. How many of the town would be loyal?

Yet maybe, keeping the ever-open mind, the man intended no harm. He seemed fresh to his job, whatever it was. He seemed fresh to most things. Perhaps he had been inside for a long time, and that made his eyes look wide. Jail? The boobery? It was a pity he hadn’t any hair to crop, as the sign for which the town was crying out. Or maybe he had come from the south with the spring, was only a halting bird of passage. Or of omen. The sun and snow here seemed to dazzle him, his mother said, keeping near the window, keeping a look-out. Even from behind her, a long way behind, he could sense her waiting for the mouth organ to start up its music again. So there was some good come of him already, he thought: he was causing her to take a little interest. He settled back comfortably in his chair and stretched out his legs. Messengers would tell him the news when there was any.

*

Phil Nagy looked up from the gasoline pump he was polishing, when Miss Purl stopped on the sidewalk in front of it. On her way home from school. Her shadow was small and sharp in the high sun.

“It looks as if the good weather’s just around the corner,” she said. “I’ll be bringing my grass-clippers over one of these days.”

“Yeah, you do that,” he said. She’d be ready for planting before anybody else, because she thought ahead. It was being educated, of course, it made you see which were the things that mattered, and then do them. He knelt down to polish the base of the pump, thinking it was handsome all right when it was clean. And bluer than the sky was these days, though not always. She must have something else to say; she wouldn’t just stand there for nothing.

“I suppose you’ve seen the stranger,” she said. He nodded. “I haven’t seen him myself. I think I must be the only one.”

“Not much to see,” he said. She’d notice in a minute he had things on his mind, and leave him quiet. Not like some.

“It was just that I expect Aunt Vera will want to have a report, and. .”

“She’s been past,” he said. “About eleven.”

“Yes? Well then, I won’t trouble you. I hope Annabel continues well.”

He nodded and looked after her walking away. Annabel was fine. She was the same as when there was no baby coming. And he was the same too, though there wasn’t anything fine in that. He ought to be different, and leave her alone. Animals didn’t do it, they left the females then, he had read all about it; it was only men did it. And knowing they did only made it worse, made it harder to stop, even though he knew it wasn’t natural. If he had an example it would help.

It was just as much Annabel’s fault, when you came down to it, but he couldn’t make her change. She wasn’t like Miss Purl, there or not there, one thing at a time; she was all over the place, and he couldn’t make her see, she only giggled. She was still a girl only. Frank shouldn’t have let her come to him, but he didn’t care either, nobody cared. If the house filled up with kids, they’d all say he was lucky. It was just the time for Ray to make jokes about this stranger looking round the town to find a good place to set up another garage. Though if he’d come to open something else, like the old hotel over the way, then maybe business would pick up. The company might even give him a new red pump as well then, though it wasn’t likely.

He couldn’t make the blue pump any cleaner, and there wasn’t anything else to do, without making something up, and Annabel was still lying up there in bed, ready for him whenever he wanted to come. He didn’t see how he was going to be able to keep himself away.

*

“Is he still here?” Mr. Fitts asked, when Hilda brought him up his lunchtime soup.

“He’s walking around still,” she said. “Why are you in bed? You’ll have sores;”

“Don’t move me,” he said, raising his hand against her. “I’ve been thinking over my wrongs. Esterhazy’s got mice down there. I didn’t sleep all night. He’s got them there to torment me. He’s trying to weaken my will.” He struggled up into a sitting position, smoothed his bedclothes for the tray and pulled down his pyjama sleeves.

“Ray hasn’t been up to shave me yet,” he said crossly. “I’ve been thinking to use my siren to bring him.”

“That’s only for if you’re dying or something,” she said, turning to leave him. “I’ll tell him you’re waiting.”

“Still walking round, is he?” he said as she closed the door. “He’d better get on with what he’s got in mind, or she’ll fix him with her old eye. Doesn’t do to look around first.”

*

Mrs. Otterdown had been waiting for the stranger a long time when she opened the door to him standing on her front steps, his breath frosting a little in the late afternoon. He was like Simon before he was old, though they wouldn’t know that, they were all long dead who might have seen that; he walked something like, and he had the same look. The sun was still strong enough to make the snow glitter behind him. So it was strong enough to melt it, it was changing the air, filling it with the smell of water. The earth would smell soon, there would be patches coming bare. That was what he was here for, she could see.

“Maybe you’ve got a room for me, ma’am,” he said.

“Who said I took boarders?” Everybody knew she didn’t. But she had seen him all day coming nearer and nearer, circling; only holding off while Harry was home for lunch. He had a blind look, as if he hardly saw most things, but he saw what he wanted all right. So did Simon. He looked at her, blinking slowly, and didn’t move. He didn’t care about her questions. “There must be those who’re glad to take a man in,” she said. “There were once. No reason why that should change.”

“It’s not for so very long,” he said. As if that made a difference. His feet would be heavy, the old boards would creak. She was old, they expected her to die and leave them in peace, she expected it herself. She was quiet, she hardly moved, trouble would be strange, like her head being wrenched. It was going to be a hot year as it was, hot and sudden; she was better off inside, waiting for the end. She couldn’t go back again now. The sun was shining on his bald head and sweat was trickling through his thick eyebrows and down along his nose. The wind seemed to have died away.

“Why are you here?” she asked. “What have you come to the town for?” She felt hot herself, even with the sun sinking down. It was nothing the last day, the last clear day, haggard and watery, and now it was burning.

“I’ve got work,” he said. He had made up his mind. There were small patches of snow still when she watched Simon from the kitchen, hammering in the morning, and brought him water and watched his throat move as he swallowed. The icicles were dripping. She was too old to make him go.

“I like my house to myself,” she said.

“It’s for four months, I figure. No more.”

“Who told you? Who said my name?”

“Jessop,” he said. Jessop. There was no reason for that. He could have left her quiet. He already had everything he wanted. “Because you own everything,” he said. “And they leave you alone. Except that field he gave me part of for my work. The field the school uses behind your house.”

That was almost honest of Jessop, keeping so near his bargain. Probably he liked to keep near, probably he felt safer with her propped in her window for all eyes to see: the public landowner. Still, reasons didn’t matter. So long as he didn’t tell Harry.

“The field is my land too,” she said. “Everybody knows that.” He only went on blinking, waiting. His whole head was glittering with sweat. He looked as if nothing could move him. “There’s only one room to choose from,” she said.

“That’ll do,” he said. He tried to move her back by moving forward, but she didn’t move back. She could still keep him there, with his legs almost touching her knees, she was still strong enough for that.

“Maybe it won’t suit you,” she said. But she could see he didn’t care, and she thought she didn’t care herself; she could still go on as she was. Whatever he did, he needn’t trouble her; at her age she probably wouldn’t even feel new feet in the house. “Well, come and see it,” she said.

He nodded, and grinned suddenly, showing two broken front teeth, and followed close after her as she wheeled herself back into the house.

CHAPTER TWO

The Indians were first, as far as anyone knew; but how long they had wandered over the country nobody knew, themselves least of all. In their own myths they had sprung from the earth like dragon’s teeth, fully grown. Their gods were nature gods and were strong, expecting sacrifices and worship, not expecting to be understood; holding different names with different tribes, wandering as they wandered themselves across the face of the earth.

No single tribe could claim the site of Otterdown without a battle, although the last to drift over it were the Crees. They had come from the eastern woodlands, leaving their canoes, to follow the buffalo like the Bloods, the Assiniboines or Stonies, the Piegans, the Blackfeet, and the Athapaskan to the north, each tribe like a squall on the face of the prairie, moved by their gods, the Sun and the Wind and the Rain, unchanging like their gods. When the buffalo was scarce they killed and ate whatever other animals they could find, or ate the roots which they knew were not poisonous because somebody beyond their memory had staked his life on them and the knowledge had been handed down, or starved.

Sometimes they scratched in a desultory way at the patch of ground on which they found themselves camped; and if seeds happened to fall there they might regard with benign incurious smiles whatever pushed its way up through the loosened soil. But if they saw that the sowing was linked to the sprouting, they saw no interest in it. Even as the seedlings grew, their camp shifted away across the prairie, following the shifting buffalo, following the will of their gods. The land was their foothold, not their living. Their only fixed points were the clumps of trees where the bodies of their dead were hung in hammocks, even then open to the wind.

When the horse came among them from the south across the endless plain, they marvelled at its beauty and mildness and swiftness, they mounted it and

pursued the buffalo, and ate more often than they had before. More again when the gun followed the horses. They slaughtered the buffalo in hundreds, proud of their skill and strength, wandering ever more widely over the prairie, tribe fighting tribe for the right to hunt the herds. But they were all doomed: after the horse and the gun came the white settler; and after that there were no buffalo anywhere. They called out to their gods, but their voices only echoed in the empty sky.

They left no mark on the town, no ghostly traces of the many times they had ridden back and forth over the patch of ground where it was to be built. Two miles to the west lay a pile of buffalo bones, the remains of a feast; half a mile to the north, another pile, smaller. These marked their claim, they said, bargaining to keep a small part of the prairie their god, the Wind, had granted them without let or hindrance. But the white settlers gathered up the bones and piled them into boxcars to be shipped to the east as a cash crop.

The Metis were transitional, but they left a few signs. Born of the Indians’ women to the white trappers and traders, they lived like the Indians on the whole of the prairie where they had been so strangely born. Some of them, feeling their fathers’ blood, settled in irregular communities, in shacks along the banks of rivers, sheltering there against the winter, ploughing a little ground at the winter’s end. But they had small faith in the life, they were their mothers’ sons, when they were not free on the prairie they were not alive. They returned to the buffalo hunt, they trapped other, smaller animals, they felt themselves to be the kings of the prairie, outnumbering their fathers’ encroaching people, rivalling their mothers’ retreating people, taking all the land as their unclaimed legacy.

When they claimed it, they lost it. They were postmen, couriers, transporters for their fathers’ people, carrying them and their possessions across the almost trackless land, the heavy wooden cart-wheels jolting over hummocks and holes. They left them on their plots of land, moving only between them, holding their own freedom. By the time they saw this endangered in the land being squared against them and their prey, their opportunity was gone. The pure-white settler was arriving in droves.

On the banks of the Rat River, a hundred yards downstream from the town, there were still some rotting boards to show where some Metis had built their shacks one winter. Mrs. Otterdown had seen them arrive, asking no one’s permission although their rebellions had failed. The next winter she saw them again. She watched them and spoke with them and waited for them in the winter after that, but they never came back. Their shacks fell apart in a summer.

But those were only a few late Metis. Most of them, grown weak and careless, had retreated to the Indians, to reserves or over the westward horizon, dwindling in numbers, their energy trickling out of them as what had been their life could not be their life much longer. Only the prairie stayed, and the sun and the rain and the wind, gods without believers.

So if a dream was to be with the town and the land round it, it had to come with the white settlers: out of eastern Canada, a generation or two settled there, or straight out of Europe, jolting with their families and belongings in carts and wagons across the grassy sea.

The first of these to reach the Rat River was Simon Otterdown. He was twenty-five, with very strong arms, bandy legs and a broad flat face. He didn’t know where he wanted to stop; all the land was open to him, one part seemed as good as another. He had been travelling over it for so long, with halts for fresh supplies which were given him in return for the blacksmithery which had been his trade, that he didn’t see how he could settle again. The longest he had stopped was for the winter before, in the village of Dauphin, from which he had come away with a girl called Brigid as his wife. She was quiet and still, and he was afraid she was already pregnant. In the back of the wagon, the sacks of grain were waiting; it was getting late for planting, he was beyond where people would want a horse shod, beyond people altogether; in a few days he knew he would have to stop.

He drove the two horses down the low riverbank, through the shallow muddy water which gurgled round the wheels, and up the other side. They had just reached the level of the prairie again, and he was gazing ahead at the slowly setting sun and the miles of billowing grass, when the back axle broke for no reason. The wagon swayed unsteadily, his wife fell against his shoulder, then straightened herself, and climbed to the ground.

They unloaded the wagon together and removed the axle. He sweated with the metal over a fire while the horses grazed under the poplar trees and his wife sat silent in the twilight. He joined the ends together and hammered them into shape, but he knew as the metal cooled that it wouldn’t bear the strain. Though he fitted the axle back in place, and bound it with stakes and rope, he did it only for pride. As the fire died down and he lay beside it with his wife, he stared up at the unending starry sky of early summer and knew that the end was almost upon him. Before dawn his wife had a miscarriage, with no apology or explanation. He buried the foetus where she asked him, in the prairie earth a hundred yards away from the river and its trees, deeply to protect it from the coyotes, but leaving no burial sign since it hadn’t been a child. The day after that, when they were able to move on, they had travelled only fifty yards beyond the grave when the back axle broke again. He climbed down from the wagon, pulled absently at the prairie grass in which his feet were entangled, and heard his wife say that the earth looked as if it would grow things. He nodded. He could see that for himself. Before winter came they were settled there in a sod hut and she was pregnant again.

So they began together what developed imperceptibly into the town. They began with a farm which for the first six years grew barely enough, over seed requirements, to keep them well-fed, and for two of those years not even so much. They had a vegetable garden, which Brigid, still as awkward and adolescent as when he first saw her, watched and cared for with a missionary zeal, even when her thin body was swollen with one growing child after another. She made it produce more than she could herself, for her first child, a girl, was born dead, and her second, a boy, flickered alive for only three weeks. Simon had to force it out of her arms while she wept in a way that he never wanted to hear again. Nine months later she had a second miscarriage, buried beside the first, after which there were two barren years when they were able to give all their strength to bringing life out of the soil, which was, as they had known, good for growing things. The vegetables flourished and, increasingly, the grain. The earth began to give back, apart from two years of frost, one early in the fall, the other late in the spring, much more wheat than they had sown. .

Gradually other settlers took up land not far from them; some haltingly, mistrustfully, assessing the prospects and the rival claims of land beyond; others wearily, gratefully. They staked their claims on the prairie in accordance with the national survey, and fenced them with strands of wire, and began to plant them. But not all of them stayed. Some were restless and others were discouraged by early failures; these gathered up their belongings and moved back towards the railroad, where towns were springing up beside the right-of-way; or they pushed on, hoping for better prospects, lurching in their wagons after the Indian over the horizon.

A sngle man, a bachelor, settled on the quarter-section right beside the Otterdowns to the west. His name was Henry Hoyt. While he was building his sod hut, he shouted to them whatever he was thinking, and he laughed. Simon watched him uneasily, and set out alone soon afterwards to establish a squatting claim to the quarter-section beside him along the river before it was too late.

The settlers helped one another and were friendly to one another, wherever they had come from and whatever they had believed, because the life was hard and there weren’t many of them. They learned by experience to hide their far families and customs and myths and private fears from their neighbours; they learned how much of what they had could be taken, and so, how much to give. They ploughed up the prairie in amity, they planted their seed and harvested what they could, and hoped that their children would lead a good life.

A road developed. Nobody built it intentionally, but the wheels of the grain-bearing carts found a common route to the railroad which ran east and wet some miles to the south. And from the town which had grown up at the railside, each settler carried back his supplies, his tools and clothes, and seed on credit if the crop had failed, since they had no town among themselves. But already the men met in the Otterdown farmyard, and the women, when they could, sent their children to Brigid to give them simple lessons, since she still had no children of her own. She sat with them for hours, her narrow face alight and her long black hair hanging in a thick plait to the middle of her back.

Then Hoyt came to talk to Simon one day, gesturing and joking and spreading his enthusiasm through the newly built frame house; and by the time he left, Simon had bought his quarter-section across the cart track, all but a small plot where Hoyt was going to live. He hadn’t the knack of farming, he said, grinning at Brigid so warmly that she turned away her head.

He began to haul supplies on commission for farmers who had no time to go to the railside themselves, and when he had a clientele he built himself a store and a room for living on the ground he had reserved. He chose his stock well and gave easy credit, and warmed people, particularly women, with his grin and his laugh and his steady stream of talk. He seemed to prosper; but on one morning late in June, after three years as a merchant, he didn’t open his store. All the provisions were there, all the bills and accounts, neatly docketed, were there, but he and his horses and wagon were gone. People waited, short of supplies, for three weeks, growing impatient, until Simon said that he would buy what was in the store, stating a price which was thought to be fair or better. As he couldn’t take over the ground, he locked the store with the money inside, built a new store for the provisions on the other side of the cart track, and established himself as the father of the town.

Some months later, Brigid gave birth, with the help of two farmwives, to a boy and a girl; and the girl, even at birth as dark as herself, lived. She was called Millie, and she grew like an animal. She followed her mother everywhere from the day she could crawl, she was dirty from morning till night, she pushed over smaller children, and she was wary of Simon, who watched her and never called her near. With her seemed to come fruitfulness, for before she was three she had a sister, and before she was five, two sisters. Then, before she was six, she died, after three days of fever which burned like fire.

Simon, his face grown round and his eyes set in webs of fine lines which came of much smiling, himself read the child into the grave, there being no qualified minister by. As many as could come from the twenty-some families living round about sang hymns in the gentle sunshine of late October, but stood well back from the small oblong hole where Brigid stood alone, allowing nobody even to approach her. With her arms folded across her breasts and her head held up to the steady morning light, she looked older than all those watching her. While her husband was reading the twenty-second and twenty-third psalms, she released her hair from the coil in which it was wound and let it flow down over her shoulders, fretted by the breeze, as she had worn it from the day the girl had been born. Then she walked away from the grave beside the graves of her other children and near-children. Afterwards they found her standing in no particular place, gazing absently at the eastern sky just above the horizon.

Her two living daughters were called Janice and Christina. They were both fair lie their father, but their eyes were brown. She looked after them carefully and gently, and when they were old enough she gave them lessons as she continued to give them to the children of the other women. She began to walk on the prairie at night, particularly when there was a moon, both winter and summer. Sometimes she was seen from farms five miles from her own, but she never called on anyone. Women of all ages began to go to her for advice.

Meanwhile, the town was growing. Two or three houses at first, all built close to Otterdown’s store, which had to be enlarged. A blacksmith from Bavaria, called Otto Grunwald, built a smithy for himself and stables for farmers shopping at the store, and for travellers on their way elsewhere. Otterdown said that he was pleased to be able to surrender the smithing which he had done for others as a convenience. At the same time he enlarged his house to make room for his wife to teach the growing numbers of children in a more regular manner.

At last the railway came, a spur line threading across the prairie to pick up the grain which the farmers could no longer effectively haul the many miles to the main line. The station was built on the right-of-way at the far side of Hoyt’s old quarter; and ‘Otterdown’, by general agreement, was painted on the hanging signboard to make the town official. More houses were built and services supplied. The farmers came in regularly and sat around in chairs in the back of the store or the front room of the smithy, warming their feet and hands in winter, making jokes away from their wives and telling each other how the country was prospering. Otterdown wouldn’t sell any of the lots in the town, but he helped people to build on them and he charged no rent at all for the first five years. He was like a father to every newcomer, ready with advice and practical help. He spent more and more time in the back of his store, summer and winter, growing fatter, smiling at foolishness, laughing at jokes, taking an interest in everyone living within reach of the town. His wife was quiet, her face weathered and fixed, her black hair always coiled to the back of her head. The new people watched her uncertainly, greeted her carefully. and thought her much older than she was. But the chief attention and energy of everyone was devoted to making a new life on the still wide-open prairie.

It was in the late spring of 1913 that Dudley Fitzgerald halted his steaming car in the main street and asked the gathering children where he could find Mr. Otterdown. He was a short man, and thin, and under his dusty driving suit very well dressed. He held out his hand to Simon and claimed the plot of land which Hoyt had reserved for himself. He showed the title deed, which he said Hoyt had lost to him, and from the following day labourers began to arrive in the town. Half of them were Chinese, lured from the laying of railway track by higher wages, and apparently happy to work from dawn to sunset; the rest were of all races and they kept the town in a turmoil with their quarrels and laughter.

The first day they demolished Hoyt’s store, and Fitzgerald distributed as bounty the money that Otterdown had left inside to pay for the provisions he had taken. The next day they began to build a hotel. They camped on the site, in tents and in the open, until the walls and roof were built and winter came; then they all ate and slept inside. Fitzgerald lived with them and watched keenly over everything they did. He was never without a waistcoat and tie, and his shirts were washed regularly by one of his Chinese workers. During the winter he was seldom out of doors; when he was, he wore a greatcoat and walked slowly around the hotel. By the beginning of spring men were carving ornaments over the front doorway and all the lower windows, and working patterns in plaster on the ceilings of the public rooms, and polishing the smooth oak floors. By the middle of May many of the workmen had gone, and those who remained were carrying furniture and furnishings from the railway station. By the end of May everything was clean and polished, and thick carpets were laid; and the last of the workmen had gone. Fitzgerald walked slowly back and forth along the balustered front porch and nodded to people who passed, and told them that, if they were interested, the hotel was now open.

There were comfortable rooms for travellers, of course, but the attraction was the bar. Men came from twenty miles and more to see the long stretch of polished oak and the glitter of a hundred bottles under the giant chandelier where the candles were changed every day. At first they gaped at the ceiling two storeys away and walked gingerly over the thick carpets, and hand-brushed themselves carefully before touching the upholstered chairs; but the drink was strong and the bartenders friendly, so by the end of the summer they raised their glasses easily to Fitzgerald when they saw him walking back and forth along the gallery over their heads. He smiled vaguely. He didn’t mix with the people of the town.

Every man could drink what he wanted for as long as he could stand; the hotel didn’t close until all had fallen or gone. Every summer night, except Sunday, candle-light and laughter and singing poured from the open doors and broad windows into the main street. Most of them went there every night, though many of them drank little and some didn’t drink at all. They went for the company and the light. It was a bad year for the crops.

But when the harvest was over, and the stubbly fields were hardening with frost, most of the men went to Regina to put on uniforms for the war. The women walked in the main street, watching the hotel which none of them liked, where the men who hadn’t gone to war had begun to gamble, and complained to Otterdown over their purchases. He agreed with them, he didn’t go to the hotel himself, but he didn’t see what could be done. Fitzgerald was within his rights. It was only a pity, he said, that he didn’t own that piece of land himself.

Then, one cold night in December, Mrs. Otterdown was seen walking towards the bright windows through the iron-hard streets only scattered with snow. The men turned from the bar and from their cards to see her standing just inside the door, not bothering to close it behind her, looking with wide eyes at the glittering cavern around her, dressed as usual all in black.

“A whisky,” she said from where she was. The men shifted uncomfortably. She walked slowly in the uneasy quiet towards the bar, her eyes fixed straight ahead of her, as if she were in a trance. “A whisky,” she said again. The barman said they couldn’t serve ladies. The men stopped drinking as she gazed blankly round at them, then up the broad oak stairs to the encircling gallery, higher than the chandelier, where Fitzgerald stood as if he had been waiting. He came down to her slowly, brushing his waistcoat and straightening his tie, to pour out the whisky. She drank it without choking and put the glass carefully back on the shining bar.

“I’ll be back tomorrow,” she said to Fitzgerald, in a voice loud enough for all the men to hear. “And I won’t be alone.”

Janice and Christina were in their early teens at the time, and looked very pretty when dressed in pink frocks as they were the next day. They were gentle girls, wanting to please; they looked frightened as their mother led them towards the hotel at suppertime while everybody watched. People followed them up the steps and watched through the doorway as their mother helped them off with their coats in the rich yellow light of the chandelier.

The hotel was empty except for the two bartenders waiting passively behind their bar, and Fitzgerald, who stood on the bottom step of the stairway, facing Mrs. Otterdown, waiting quietly, his pearl stickpin glowing in the candlelight. She gazed round the enormous room, her expression almost childlike, while her daughters clung to her coat.

“Who would have thought it would grow into this,” she said at last. “A little piece of land.”

“Hoyt was nothing to do with me,” Fitzgerald said. “I only took over the land. All that’s here is of my making, all of it. And you have no right to. .”

“They won’t come here anymore,” she said quietly, and put her daughters coats on again and took them home.

For six months after that the hotel was open every day, but nobody drank there. Children ran in and called names and laughed and ran out. Fitzgerald continued living there alone, always immaculate; and when he walked back and forth along the front porch, he was always courteous to anyone who passed. Not until June, when the legislature closed all the bars in the province, did he quietly padlock the doors and board up the windows and climb into his car and drive out of the town. It was rumoured that he had returned years later to hang himself from his chandelier, but nobody knew for sure, because the hotel had never been seen open since the day he had left.

CHAPTER THREE

Harry leaned against the cash register in the back of his store, poking at the keys with his fingers, sounding out the notes in his mind through a secret transcription; for Maida the machine only rang up sales. He kept his ears on the men round the stove behind him, and his eyes on a family of Hutterites who were gathering goods into their arms; the father, he suspected, had been trimming his beard. The world was in a sad way.

“I just wish he’d get to work on it,” Rupe Windflower said, his voice high, an easy voice to know. “It’s this waiting.”

“How’s he supposed to till it thaws?” asked Alvin Gleave.

“He could be measuring the ground at least. Hammering in stakes, something like that,” said Ephraim Ledbetter, his voice deep and low. “Since the snow’s pretty well gone.”

“He could be friendly since he’s here,” Archie Dworshak said. “Come and give us an idea, like, what he’s got in mind.”

He could tell them more than that one word, Hank, which he called his name, Harry thought, taking their part. There were a dozen of them around the stove behind him, enough for a quorum, and he could feel the pull of claim in their voices; they wanted his opinion, his support. He shifted his feet so that his back would look reassuring. He thought that his duty stretched further than that, but he wasn’t ready to pursue it. He was out of practice after a number of easy years and, after all, appearances too were important. His father could agree to that.

“It’s only that he makes me nervous, watching me the whole time I’m painting the roller,” Rupe said.

“He’s been watching me in the grease pit,” Phil Nagy muttered, just loud enough to be heard. “He keeps picking things up and saying he could use them.”

“Looking round at Annabel the same time,” Ray Keefer said; he was a sly one all right, he could wink with the best of them. “Some of the women cross the street when they see him coming.”

“There’s no need for that,” Alvin said. “Willa says hello to him regularly.”

“My wife says there’s something eerie about him all right,” Lon Esterhazy said. “She don’t like the way he looks at her.”

“You think maybe he wants to use the roller for this tower?” Rupe asked, his voice uneasy. “Maybe I could work it for him, but what’s he want it for? It’s got no traction. If it was a caterpillar, I could see him hanging around.”

“On Sundays, Iris said, it’d be a big danger to the children,” Humphrey Wilkinson said mildly. “Said her husband said so. Could be, too, when you think of it. They’d maybe climb up and fall off and break their necks.”

“Specially where it’s going to be,” Ron Macnamara said. “Can’t say I blame Overgaard for being angry, losing nobody knows how much of the playground.”

Harry watched the Hutterites coming towards him to pay. He didn’t suppose they would be interested, after holding out so long against everything with their peasant costumes and patriarchy, if he told them that a strange man had come to build a water tower in the town. Probably they wouldn’t see in what manner he was strange; all who were not Hutterite were strange. He smiled at the father and the mother and the three small sons, and stood at ease, as if he hadn’t heard MacNamara’s oblique criticism, as if he didn’t know that they were all glancing at his back, all uneasy and fretting and knowing there was nothing they could do: if his mother wanted the tower built behind her house, that was her privilege as landowner; so much the worse for the school, if it was worse. So was it her privilege to lodge the man in her house, in the bedroom next to his own, a thin wall only between, so he could hear the mouth organ playing softly, in tunes he knew and didn’t know, when everybody else was asleep.

“You’d think he came here to burn the town down, instead of giving it something we can all do with,” Alvin said.

“If he gets round to doing it,” Frank Chopek said.

“Where’s the water coming from when he does do it?” Ledbetter asked.

“We got enough wells as it is,” Esterhazy said.

“Won’t help the fields,” Dworshak said.

“He’ll pump water up from the river, in the spring,” MacNamara said. “I got nothing against the idea.”

“It’ll make for extra work,” Alvin said.

“There’ll be nothing to pump the water into, this spring,” Wilkinson said. “Maybe he should have started it last fall.”

“Maybe he couldn’t, last fall,” Ray said. “Maybe he was busy somewhere else.” There was something odd in his tone which seemed to silence them all for awhile, so that all Harry heard from them was their breathing and the creaking of their chairs. The Hutterite were leaving as quietly as they came, calling on him for nothing but goods, serving under another system, another government. It was peaceful to watch them come and go in the middle of his neglected duty. Maida was standing by Mrs. Paradis, the only other customer, as she sorted through a pile of plastic plates. Ray was the clever one, they all said so; but they listened to MacNamara when they listened to each other at all. His own best course was to invoke his father’s shade and keep easy and count his blessings: his mother had looked as if she would die and now she didn’t, at least not for a while.

“Somebody was saying he’s been in the town before,” Wilkinson said.

“Before my time, then,” MacNamara said.

“If he wasn’t,” Phil said. “It’s queer him coming here now.

“Maybe as a young fellow he was,” Ledbetter said. “I don’t remember so well”

“Family moved away, maybe,” Esterhazy said. “In the thirties, maybe.”

“Well, I got no objection to him being here,” MacNamara said. “Whatever he’s here for, as long as he don’t cause no trouble.”

“He tried to talk to Bella in the street this morning,” Ray said. A warning for them not to rest easy. “Phil saw him.”

“She was looking a treat, Bella was,” Rupe said. “She came round to see how the paint job was getting on. Said it marked the beginning of spring for her when I first took the roller out. Something was bothering her though, I noticed that. But she didn’t say anything.”

“It was just surprise, she said, made her tell him to go away. Because he was a stranger,” Phil said.

“Seems to me her mother had time to warn her she might bump into him,” Ray said.

“If he tries anything of that kind,” MacNamara said. “We’ll soon get him out of town. Water tower or no water tower. If he don’t respect things the way they are.”

“We could always build one ourselves, I guess, if we wanted,” Ray said.

“Old Simon always said a water tower’d be the making of this town,” Ledbetter said. There was a calming word. If old Simon said so..

“That’s what I say,” Alvin said. “He’s got the whole thing worked out, blueprints and everything. We ought to give him a chance.”

All they wanted, Harry thought, was for him to say something, just something, as the landlord’s son and heir. He could say he was for the tower or against it, or that Bella wasn’t to be touched by strange men; nothing more. He had only to turn and face them and, like his father, be amongst them, persuasive and soothing, saying that Hank talked to him of nights through the wall they shared, about his dream of bringing water to a parched community, or one he had thought was parched. He could invent a history for Hank, and a satisfactory surname. His father would even have convinced them that the tower was really a community effort. It was a pity that he wasn’t his father, since he was left with his father’s role; left to explain why his mother had taken the man into her house, away from them all, making no claims that she cared what any of them thought or did, so long as they left her alone and paid her rent. Daily the gap between Hank and them was growing wider, and only he, as vizier was left to bridge it; which he felt unfit to do. It was a painful stretching of his quietude, which had taken some years to form.

Still, the change was rousing her, his mainstay; that was good. And the man might yet be no problem, though they had all decided he was, so why so uneasy? They could sit round his stove on his chairs in his hereditary store until doomsday, and call up the shade of his father for comfort and guidance, and still he need do nothing but stand near them, not even facing them, showing them only his easy, unworried back. If they were discontent with that, they would have to settle on a plan; if they wanted to depose him for inaction, they would have to choose a leader and a dagger and a time. And then face the vengeance of the old queen? Their debts called in, foreclosures sent out. Oh, he was a lucky one, with his caul and all.

They weren’t talking much now. Some of them had gone outside. Mrs. Paradis had gone, and Maida had gone to answer the telephone in the post office. It seemed they had stopped expecting his opinion; they were satisfied just to sit round his stove. But the question was still there. He ought to try out some kind of answer, at least for the sake of form.

All right then: did he, himself, object to the water tower being built in the town, smack in the middle of his inheritance? No. He approved of it, if anything. It would be useful even if it wouldn’t be handsome; and, after all, nothing had been built for beauty in the town from the beginning, except the hotel, and that hadn’t come to much, so maybe it was as well that the tower was for use. Any new building was good for the town; it brought in money and raised people’s spirits. As the reeve, he gave his blessing. Provided only that the hotel was left as it was: a minor rider to the agreement, nobody but himself would care.

But the question was further: did he object to the location of the tower, not wanting it so near his house or, more generously, not wanting the school playground to be diminished? No. Or did he think that the man was a threat to Bella’s virginity or to the general peace of the town, and if he did, did he care? Well no, it wasn’t that, not exactly that, that was a side part of his duty, the question was elsewhere.

The question was right in front of him, he didn’t need to hide it, he was long grown up now, even beginning the slow decay.. He was digressing; he was unsettled, he must keep his back and shoulders easy, they were waiting for his weakness to show, whispering round from chair to chair in the half-darkness of the dying afternoon. All he had to say was that he shared their doubts; they would still worry, but they wouldn’t worry him. But he couldn’t manage that. His doubts were all his own, and not so smooth with years of handling as he had thought.

What he should tell them, if they got round to asking, was that he would feel a good deal better if they all filed out of the store, away from his unsheltered back.

He was becoming nervous. It would show. He gazed straight ahead of him at the empty store and fingered the cash register keys gently. He was troubling himself about nothing. Probably the uneasy feeling he had had for the two weeks this man Hank had been in the town would settle in good time, as feelings generally did. Maybe, as they said, when the ground was all thawed, soon now, and he really began building his water tower, all apprehension would die.

But then what happened to the question which wouldn’t change? It might as well be a water tower as not a water tower, since Hank was building it to build; that was clear enough. And it might as well be built in the town as out of it or in some other town or city; it could at least be useful here. Then? Then?

The voices of the men behind him were blurred by the faint buzzing in his ears. He was as good as alone. Then he ought to ask himself directly, and answer, why he wasn’t building a water tower himself. There was a sense of duty for his father; not a new sense either, though it jangled now like new. But, even so, the answer was final and , if it was depressing, well, it was his question and his answer; if he didn’t build a water tower and never had and was never likely to, for any reason, because he didn’t feel he wanted to, then that was simple enough. If he minded after that, he had only himself to blame. He smiled his broadest smile at the empty store in front of him; yes, he minded. Doubtless he was cursed.

*

Jessop sat on his usual stool, furthest from the window, watching his coffee spin round with the spoon. Hilda didn’t fret him; she let things go as they would. Even if she had thought anything was out of the usual, she seemed to have stopped thinking it now. Josey was more of a problem; he pretended he wasn’t interested in anything except the food in front of him, but his eyes flickered all along the counter. Though the trouble wasn’t yet, it was quiet yet.

“You got an opinion on him?” he asked Hilda, letting go of the spoon so it was carried round the cup by the coffee, and watching her straighten her back from the sink. “Everybody’s got one, far as I can make out. Keep changing them too. One day you hear one thing, next day another.” She pushed back her hair with a soapy wrist and looked at him in the mirror. Josey was looking at him too. What was in what he said? It was like they had antennae, not just eyes, to notice things. If they did find out and the word spread that he was behind it, that’d be the sure end of what small peace he had. He never should have gone to Maggie when she asked him, that was his first big mistake. If he hadn’t gone to her he wouldn’t have promised her. “I guess we’ll all see what it’s about soon enough,” he said, flatly, to turn them off.

“He has a look like he lost his way,” Hilda said. He blew gently into his coffee, as if he didn’t hear. The thing was not to show any interest. Then they could watch Hank all they liked and the only person they’d see behind him, like it was all her doing, was old Mrs. Otterdown. He’d be as safe himself from their eyes and tongues as if he was in his own earth room. Let them see her. And Harry. And leave him alone. He wouldn’t even be in this place, or any one place such a deal of years if it hadn’t been for Maggie calling when he thought he was too far to hear.

That was what made him think there was no harm in going to see her, just to see her. Since he was so far, and she was getting old and tired. And the next thing he knew her big hands were out, as usual, grabbing him. And making him promise the way she always did, crying and holding him and telling him he knew best and could do best, that if he had the money he would hold onto it and turn it into more, against the time and need. And he had, that was what he had done all right; and all she had done was get drunk on a cold night, the way they always said she would. They were glad if anything.

“I was thinking. I didn’t hear,” he said. Hilda’s black eyes were looking at him out of the mirror.

“It’s to Josey I was saying,” she said. “If he wanted any more.”

It was the spring not coming, he thought. When he had thought it would. It was this cold closing down again. When he could get out on the prairie he’d be all right, he’d be quiet then. He wouldn’t mind anything when plants were pushing up everywhere out of the soft earth, all kinds of green and smelling and their roots wet and stretching in his fingers. They could do what they liked then. And by the time the next winter came it would all be over, one way or another, and whatever Hank did or didn’t do Maggie couldn’t make him promise anymore. He could go off wherever he wanted then and leave this town to rot. If only they didn’t find him out before.

CHAPTER FOUR

The church was white, with a steep roof of reddish wooden shingles and a steeple like a short jousting lance. It was forty-some years old and attached to the rites of the United Church of Canada. People had tried at certain times to organize other forms of worship at one farmhouse or another, but none of them had endured. The present minister, Archibald Fairling, had been a Methodist before the Act of Union. He was an elderly man now, but still vigorous; in most weather he walked about a good deal in the town. Both the manse-which he shared with his housekeeper, Mrs. Watson, and her daughter, Bella-and the church itself stood on ground donated by Mr. Otterdown.

The first church ever built on this part of the prairie had been, as was usual, of sods. It had been an appendage to the house of the third farmer to arrive, a man called Esterhazy, later the father of a large family who drifted one by one away to towns, except for the youngest son, who established a seed store opposite the derelict hotel and sold the farm to migrating Ukrainians when his father was dead. It was better than average land, but all the land was good.

The service in Esterhazy’s church was, in principle, non-sectarian, but in feeling not so pallid, for Esterhazy was the son of an Ontarian Presbyterian circuit rider and, though he tried to restrain himself, he had inherited the flair. Nobody minded this at first; everybody was pleased to have some place for common worship. But eventually, as Esterhazy’s intensity began to slide into mysticism and the service began to lose what regular shape it had had, people grew discontented and asked each other why Esterhazy should be allowed to play God. So that when Otterdown said he had located a qualified minister, and offered to accommodate him in his own house and furnish as a church the back room of his newly enlarged store, there was general relief. Esterhazy came with the rest of them, but gloomily, and drove all the way to the railside when he needed supplies.

This church was inaugurated in the spring by the Reverend Mr. Keefer, who stood on the front step of the corner entrance to the store to greet the congregation, blinking his owl eyes in the strong sunlight. His wife, born in Poland, stood squarely beside him to shake every hand in her own broad flat one. Their wagons parked side by side in the street, the settlers made their way uncertainly toward the doorstep, themselves smiling and welcoming, their children by their sides or in their arms. Whatever secret beliefs they had carried with them out onto the prairie, they didn’t talk about; it was enough that they could make their way through the dark aisles of Otterdown’s store, past the piles of familiar weekday goods, to something like a real church at the back, where chairs and a lectern had been installed.

Mr. Keefer was a simple preacher and a kindly man. He was much regretted when he died of pneumonia four years later. At his own request, his body was shipped to his sister in southern Ontario. But his wife, who had given birth only a few months before to a son, her first child, said that she had nowhere to go herself. She was strong and young, but her English was still not good. For some years she lived on the homestead of a German family.

From then until long after the Great War, the town had no resident minister. Itinerant preachers of all denominations passed through, sometimes even staying for a month or two if travelling was difficult or the man himself was tired. The last to stay did so to bury the victims of the influenza epidemic which swept through the town in October of 1918. Three people were feverish on the night of his arrival, and more than twenty had fallen sick by the following Monday. He conducted no service, for everyone kept fearfully to his house, but he visited and he comforted, taking with him a woman they called swarthy once she had gone, whom the minister said was French Canadian and who evidently had much Indian blood. She also had been trained as a midwife and nurse, and her solemn face soothed their panic. They learned that her last name was Laframboise, but they called her by her first, Helen.

Although more than a third of the people living in the town and around it were stricken, only three died, apart from the minister himself, whose body was preached over by Esterhazy while the other mourners froze.

The three apart were Janice and Christina Otterdown, and a man called Palmerston, who, though much older than either of the girls and long a bachelor, farming some fourteen miles from the town, had become engaged to Janice. He was at least a few years younger than her father, and as they had walked round the town together to tell people they had both seemed quiet and happy. He had been the first to die, Christina the last. The minister had lived long enough to bury them properly, while Otterdown cried like a baby. Nobody could think what to say to his straight, silent wife, who heard out the service and then led him away. The house which had been built beside theirs for their daughter and son-in-law remained empty for thirty years. Helen Laframboise stayed on in the town as general nurse and midwife, living in two rooms, not very cleanly, over the cafe.

In the following spring the foundation was dug for the present church. To be a memorial, Otterdown said, for those who had died in the war and at home. Over the concrete basement seasoned timbers were raised, double walls and roof fixed securely in place against the winter, a steeple raised over the roof and a bell hung in the belfry, all under the careful supervision of Otterdown who was paying the greater part of the cost. Both the church and the manse beside it were completed by the time the first snow fell. In mid-November the bell rang out through a cold, cloudy morning for the first, inaugural service, taken by an itinerant Methodist minister returning east after seven years of preaching to farmers newly placed on the prairie. Warmed by the glowing stove behind the large central pulpit, he delivered a strong sermon on the power of God to the congregation which was packed together between the roaring side-aisle stoves. They followed him in prayer and sang the hymns as loudly as they could, and shook him eagerly by the hand when the service was over. The next morning everybody saw him to the eleven o’clock train, the only one out of town, and waved until he was gone. Afterwards, they forgot his sermon and even his name, but for a long time they liked to remember the occasion. It was better than kneeling alone under the blank face of God.